[ad_1]

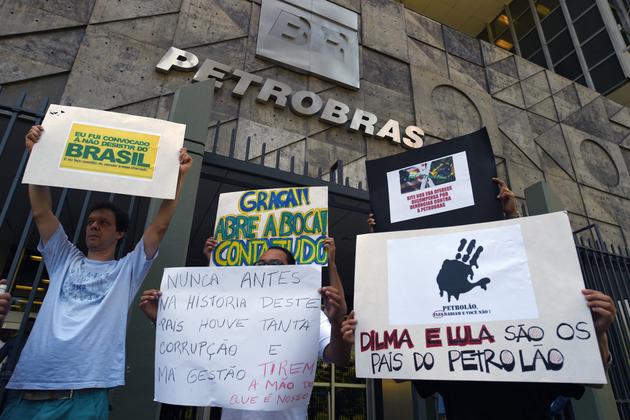

Something is rotten in the state of Brazil. The entire country is being hit by a series of simultaneous crises, a kind of perfect storm – economic recession, environmental disasters, extreme political polarization, Covid-19… and now the sinking of the judicial system. Another thunderclap in an already heavy sky that had nevertheless been filled with hope seven years ago, when a young judge named Sergio Moro had launched, on March 17, 2014, a vast anti-corruption operation called “Lava Jato” (“Car Wash”), involving the oil giant Petrobras, construction companies and an impressive number of political leaders.

In one fell swoop, the impetuous man and his team of prosecutors, supported by the judiciary and the media, were going, at last, to clean up and save Brazil! Numbers were impressive: 1,450 arrest warrants were issued, 533 indictments filed and 174 people convicted. No less than twelve Brazilian, Peruvian, Salvadorian and Panamanian heads of state or ex-heads of state were implicated. And the colossal sum of 4.3 billion reais (610 million euros) was recovered to the public coffers in Brasilia. Even former President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, adored by a majority of Brazilians, could not resist the wave, as he found himself behind bars.

And then suddenly, nothing, or almost nothing. In less than two months, the sprawling investigation collapsed like a soufflé. At the beginning of February, the federal Public Prosecutor’s Office announced the end of the “Lava Jato”, dismantling its main team of prosecutors with a coldness that was unheard of. Then a Supreme Court justice ordered that the charges against Lula be dropped. Fifteen days later, on March 23, it was the turn of Brazil’s highest court to rule that Judge Moro had been “biased” in his investigation.

Irregularities and confusion

The world’s largest anti-corruption investigation, as one Supreme Court justice called it, has become the biggest judicial scandal in the country’s history. After more than seven years of proceedings, the very heart of the Brazilian justice system has just disavowed the form and substance, opening up an abyss of questions about its methods, its means and its choices.

Certainly, the news site The Intercept – created by Rio de Janeiro-based American journalist Glenn Greenwald and Silicon Valley billionaire Pierre Omidyar – has not stopped pointing out the irregularities and errors in the investigation over the past two years.

One hundred and eight articles published to date have, in turn, lifted the veil on the compromising messages exchanged between the prosecutors and Judge Moro, shed a harsh light on the links maintained, sometimes outside of any legal framework, by Brazilian prosecutors with agents of the US Department of Justice (DoJ), and highlighted the political bias of certain members of the “ Lava Jato ”, obsessed with the idea of blocking the Workers’ Party (PT). The very serious and independent Agência Publica, the investigative journalism agency founded in São Paulo by women reporters, also showed how the proceedings were marred by irregularities and numerous confusions. After these striking revelations, there remains a strong taste of unfinished business, the sensation of a failed trial and an ontological mess for an investigation that was meant to be a model of its kind.

To try to understand these reversals and successive twists and turns, we must go back to the origins of this political and legal drama. Set the scene and understand how its main actors found help and a legal framework from jurists and influential figures, first in Brazil, then from agents of a North American administration eager to continue its work of rapprochement with its big southern neighbor.

When Lula became president in 2003, he knew that he was expected to do something about the fight against corruption

Months of investigation, interviews and research were necessary for Le Monde to set the scene behind the scenes. While some areas remain in the shadows, some episodes of “ Lava Jato ” highlight unmentionable complicities. Others, on the contrary, reveal how certain judges and prosecutors have sometimes used their independence – quite real – in the service of a political project, by embarking on a mad dash, establishing motives, means and denials. “ It was like a ball thrown into a game of skittles, ” admits anonymously a former close associate of the Obama administration, in charge of judicial matters related to South America. A “ game ” that turned into a trap.

When he took over as president of the Republic in 2003, Lula knew that he was expected around the corner. Especially when it comes to the fight against corruption, an old demon in Brazilian politics and one of Lula’s main campaign arguments. He thus entrusted his new Minister of Justice, Marcio Thomaz Bastos, with the task of reforming the judicial system, while accepting the appointment of a prosecutor appointed by his peers as head of the Public Prosecutor’s Office, whereas his predecessors were used to choose people more accommodating with power.

One of the first concrete expressions of this commitment is the creation of courts dedicated to the fight against money laundering and organized crime. Sergio Moro will be among the first judges appointed to head these courts. At the same time, a national strategy to fight money laundering and corruption is being put in place with the assumed objective of “ facilitating informal exchanges ” within the administration, and making the investigation of cases more efficient. The young magistrate based in Curitiba, in charge at the time of the Banestado case, an investigation into money laundering within a regional public bank, is among the most fervent supporters of this strategy, which makes it possible to obtain tax and asset information more quickly and share it with various authorities, including foreign ones.

Fear of terrorism

It is true that in the world of international judicial cooperation, the fight against corruption, money laundering and terrorism holds a special place. In the aftermath of the September 11 attacks, the United States is seeking by all means to neutralize future attacks, particularly by targeting the financial networks of these organizations. However, in Brazil, U.S. intelligence is worried about the presence of possible units of Hezbollah, the Iranian-backed organization that has long been on the U.S. blacklist, on the triple border between Argentina, Paraguay and Brazil.

The Bush administration seeks to increase Brasilia’s counter-terrorist action, which at the time politely refused to do so. In order to get around the coldness of Brazilian officials – who consider that the terrorist risk is deliberately exaggerated by the United States – the US embassy in Brasilia tries to create a network of local experts, able to defend American positions “ without appearing to be pawns ” of Washington, to use the Ambassador Clifford Sobel’s phrase in an American diplomatic cable that Le Monde was able to consult.

Sergio Moro, who is actively collaborating with the US authorities in the Banestado affair, is then approached to take part in the State Department’s International Visitors Program. He accepts. A trip was organized to the United States in 2007, during which he made a series of contacts within the FBI, the DoJ and the State Department.

In two years, the U.S. embassy in Brasilia built a network of judges and prosecutors convinced of the relevance of using us techniques

The US embassy seeks to push its advantage. In its desire to structure a network aligned with its orientations within Brazilian judicial circles, it has created a position of “ resident legal advisor ”. Karine Moreno-Taxman, a prosecutor specialized in the fight against money laundering and terrorism, is chosen.

Since 2008, this expert has been developing a program called “ Projeto Pontes ” which, under the cover of supporting the needs of the Brazilian judicial authorities, organizes training sessions allowing them to take ownership of American working methods (anti-corruption task forces), their legal doctrine (plea bargains, in particular), as well as their willingness to share information “ informally ”, that is to say outside of bilateral judicial cooperation treaties.

The Embassy has been holding a number of seminars and meetings with judges, prosecutors and specialized officials, focusing on the operational aspects of the fight against corruption. Sergio Moro participates as a speaker. Within two years, Karine Moreno-Taxman’s work bore fruit: the Embassy built up a network of judges and lawyers convinced of the relevance of using American techniques.

In November 2009, the Embassy’s legal advisor was invited to speak at the annual conference of Brazilian federal police officers. The meeting was held in Fortaleza, a seaside town in northern Brazil, where nearly 500 law enforcement, security and legal professionals were invited to discuss the theme of “ fighting impunity ”.

“In a case of corruption, you have to systematically and constantly chase the king to bring him down”, according to the legal adviser of the US embassy in Brasilia.

Sergio Moro is there, present from the first hour of the conference. He even opened the discussion, just before giving the floor to the North American representative. Visibly in good shape, the judge from Curitiba starts by quoting the former North American president Franklin Delano Roosevelt, then he attacks in no particular order the white-collar crimes, the inefficiency and the flaws of a Brazilian justice system that is sick, according to him, of a system of “ infinite appeals ” that is far too favourable to the defence lawyers. He called for a reform of the penal code, underlining the fact that discussions in this sense are taking place at the same time in the Brazilian Parliament. Applause from the audience.

In front of the audience, Mrs. Moreno-Taxman takes her place. She spoke in a tone of voice that was much less dry and serious than that of her predecessor, but just as direct: “ In a case of corruption, ” she said, “ you have to systematically and constantly go after ’the king’ to bring him down ”. More explicit: “ In order for the judiciary to condemn someone for corruption, it is necessary that the people hate that person ”. Finally, this: “ Society must feel that this person has really abused his position and demand his conviction ”. Again, applause from the audience.

The name of President Lula, entangled in the “ Mensalão ” scandal, the bribe and vote-buying affair in Congress, which came to light in 2005, is not mentioned at any time. Even though he is in everyone’s mind, no one imagines that he will become the “ king ” designated by Mrs. Moreno-Taxman. However, this is what will happen.

Illegal eavesdropping

For now, the Petist government sees nothing coming. Three months after the Fortaleza meeting, instead of carrying out political reform to put an end to the illegal financing of electoral campaigns, it prefers to pledge public opinion by presenting an anti-corruption bill. He thus hopes to respond to recurring criticisms since the PT came to power and gain influence on the international scene by complying with OECD standards, where the OECD Working Group on Bribery in International Business Transactions, which is heavily influenced by the United States, is pushing Brazil to reform its legislation in this area.

Sergio Moro, on the other hand, is taking a public stand in order to toughen the penalties provided for in the bill and ensure that plea bargain is adopted as a valid legal instrument. The man who has become one of the figures of the Brazilian debate on money laundering issues uses borderline legal methods – usurpation of the prerogatives of the prosecution, instruction of preventive prison orders despite the opposition from higher authorities, wiretapping of lawyers or personalities with immunity – and thereby arouses the mistrust of some of the magistrates.

“Crimes linked to power are by nature, in view of the position of their perpetrators, difficult to prove through direct evidence”, hence “ the greater elasticity in the acceptance of evidence by the prosecution”.

Sergio Moro, however, was appointed, in early 2012, assistant judge to Rosa Weber, recently appointed Supreme Court justice. The latter, a specialist in labor law, wanted to have a criminal law expert to assist her in the final judgment of the “ Mensalão ”. The Curitiba magistrate will write part of the justice’s controversial decision on the case. “ Crimes related to power are by nature, in view of the position of their perpetrators, difficult to prove through direct evidence ”, hence, specifies the text, “ the greater elasticity in the acceptance of evidence by the prosecution ”. This precedent will be taken to the letter by Sergio Moro and the “ Lava Jato ” prosecutors when Lula was accused and convicted.

The gear began in 2013. Brazilian parliamentarians, who had been debating the anti-corruption bill for three years now, decide to vote in mid-April. To look good in front of the OECD working group, they include most of the mechanisms provided for in a US law, which is beginning to be talked about in European business circles: the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act (FCPA).

Created in 1977 following Watergate, this law’s main objective was to combat acts of corruption by American companies abroad, by imposing financial sanctions. Until the end of the Cold War, it was rarely applied. Everything changed in the 1990s. The Clinton administration began reforming the FCPA, which went hand in hand with the adoption of an anti-bribery convention within the OECD, in order to “ multilateralize its effects ”, according to a diplomatic cable from the American embassy to the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). The law’s jurisdictional criterion is what stands out: any company having any connection whatsoever with the United States and having paid a foreign official for corrupt purposes can be indicted. Any connection means the transit of funds through a U.S. bank account, or the transmission of an email whose server is located on U.S. soil.

In fact, almost every company in the world is exposed to the law, especially those competing with U.S. companies for large contracts, such as arms and equipment sales, construction and financial services. This development will lead to an increase in penalties related to the implementation of the FCPA: from a few million dollars in the 1990s, we go up to several billion in the 2010s. And in this context, Latin America in general and Brazil in particular will interest DoJ prosecutors.

Infringement of procedural rules

The latter, who depend on the executive branch, although they are considered to be “ autonomous ” from the rest of the US administration, know that the upcoming implementation of the Brazilian anti-corruption law will allow them to sanction Brazilian companies under the FCPA. In November 2013, at the FCPA Conference, an annual meeting of leading figures in the U.S. legal community, DoJ Assistant Attorney General James Cole announced that the head of the department’s FCPA unit would be traveling to Brazil shortly, to “ train Brazilian prosecutors ” on the use of the law.

At that time, Sergio Moro takes up an old money laundering case, linked to the “ Mensalao ”, which he had left lying around since 2009. It concerns the relations of several crooked intermediaries (Carlos Chater and Alberto Youssef), with José Janene, congressmen of the Progressive Party (right-wing party and member of the government coalition). The Curitiba judge is interested in the investments of the two businessmen in the company Dunel Industria, made through the bank accounts of a gas station called “ Posto da Torre ”, in Brasilia. At Mr. Moro’s request, Chater was wiretapped from July to December 2013: the aim was to find out whether these investments were used to hide possible money laundering acts in favor of Mr. Janene.

It is by making the link between Dunel Industria, headquartered in the state of Parana, and the gas station, through which transit large sums of money, including for some Petrobras executives, that Sergio Moro claims his competence to handle the case. Curious manipulation: most of the acts of money laundering and corruption of Mr. Chater and Mr. Youssef takes place in São Paulo. According to Brazilian criminal procedure, this should have led to a judge from that jurisdiction handling the case – not Sergio Moro.

But the Curitiba magistrate understood the intricacies of the Brazilian judiciary. He knows that by concealing the location of these front companies, he will be able to keep control of the investigation. On the condition that the higher courts allow him to do so. And this is what is going to happen, despite this breach of the rules of procedure.

Seducing the public

From August 2013, some legal experts saw the danger arising by the implementation of the new anti-corruption law. A premonitory note, published by the very serious American law firm Jones Day, predicts that it will have deleterious effects on the Brazilian justice system. It warns against its “ unpredictable and contradictory ” functioning due to its “ politically influenceable ” nature, as well as the lack of “ approval or control ” proceedings. According to the document, “ each member of the Public Prosecutor’s Office is free to initiate a case according to his or her own beliefs, with little possibility of being prevented by a higher authority ”.

Despite the warnings, the government and its allies are moving forward. President Dilma Rousseff, still trying to appease an increasingly critical public opinion, has even decided to tighten the criteria of applicability. Parliamentarians believe that this law will not affect them more than the previous ones.

After six months of investigation, the judge in Curitiba had enough evidence to issue the first arrest warrants. On January 29, 2014, the anti-corruption law came into force. On March 17, the “ Lava Jato ” task force was formally constituted by the Attorney General of the Republic, Rodrigo Janot. As its head, he appoints prosecutor Pedro Soares, who is opposed to Sergio Moro’s handling of the case, since Alberto Youssef’s alleged crimes had taken place elsewhere than in Curitiba. His approach will fail. He will be replaced by another prosecutor, 34-year-old Deltan Dallagnol, who not only supports Moro’s handling of the case, but will also become the magistrate’s main supporter.

For the United States, it’s about reducing Brazil’s geopolitical influence in Latin America, but also in Africa

Since its inception, “ Lava Jato ” has attracted media attention. The orchestration of the arrests and the pace of the indictments by the prosecutors and Moro turned the operation into a real political and judicial soap opera. As Brazil prepares to embark on a presidential and legislative campaign, the country’s political and economic elite suddenly seem terrified at the idea of being swept away by this endless cascade of revelations, as the list of influential figures under scrutiny grows longer.

At the same time, Barack Obama’s administration is seeing an increase in protests from allied countries, first and foremost France, which is concerned about the increase in sanctions imposed by the DoJ in the fight against corruption, targeting certain national flagships such as the Alstom group. In order to signal its political support for the anti-corruption actions undertaken by its government, the White House published a “ global anti-corruption agenda ” in September 2014. It states that fighting foreign corruption (through the FCPA) can be used for foreign policy purposes, to defend national security interests. A month later, Leslie Caldwell, then DoJ Assistant Attorney General, delivers a speech at Duke University clarifying this direction: “ the fight against foreign corruption is not a service we provide to the international community, but rather an enforcement action necessary to protect our own national security interests and the ability of our American businesses to compete globally ”.

On the South American ground, the rapidly expanding Brazilian construction giants Odebrecht, OAS or Camargo Correa have entered the crosshairs of the North American authorities. Not only because they are winning more contracts, but also because they are taking part in strengthening Brazil’s geopolitical influence in Latin America and Africa by financing, illegally in most cases, the electoral campaigns of personalities close to the PT, led by the party’s main communications consultant, Joao Santana. In 2012 alone, the electoral strategist, comfortably financed by Odebrecht, organized three presidential campaigns in Venezuela, the Dominican Republic and Angola, not to mention the municipal elections in Sao Paulo. All of them were won by the candidates of the Brazilian publicist Santana.

Goodwill Pledges

In front of several journalists who are members of the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (ICIJ), Thomas Shannon, American ambassador posted in Brasilia from 2010 to 2013, stated that the Brazilian political project of economic integration of South America raised serious concerns in the State Department and that the latter “ considered the development of Odebrecht as part of the power project of the PT and the Latin American left ”. Concerns that are all the stronger as the episode of the revelations of the whistleblower Edward Snowden, in August 2013, concerning the spying of the US National Security Agency (NSA) against Dilma Rousseff and Petrobras, clearly threw a chill between Brasilia and Washington. “ If we add to all this a rather bad personal relationship between Barack Obama and Lula, and a PT apparatus that is still as suspicious of its North American neighbor, we can say that we had work to do in order to redress the situation, ” recognizes a former DoJ member in charge of Latin American cases.

Multiple levers of influence are activated. There is the FCPA and the networks of prosecutors and judges trained in investigative techniques put in place in recent years. To achieve its ends, the DoJ is using a major lure: the sharing of fines that will be imposed by the American authorities on Brazilian companies under the FCPA.

In order to give pledges of goodwill to the U.S. authorities, Brazilian prosecutors organized a confidential visit to Curitiba on October 6, 2015, by seventeen members of the DoJ, the FBI and the Department of Homeland Security to receive a detailed explanation of the ongoing proceedings. They allow them to have access to the lawyers of the entrepreneurs potentially brought to “ collaborate ” with the US courts, without the Brazilian executive power being informed. But this comes at a price: each of the fines imposed on Brazilian companies under the FCPA will have to include a share for Brasilia, and also for the “ Lava Jato ” operation. The Americans accept. With this deal done, Brazilian prosecutors will go fishing for companies that may fall under the DoJ’s purview. In addition to Petrobras and Odebrecht, they will go after subsidiaries of SAAB, Samsung and Rolls-Royce.

“Agents need to be aware of all the potential political ramifications of these cases, because international corruption cases can have major effects that influence elections and economies”, said an FBI official.

With her parliamentary majority melting like snow in the face of the growing number of corruption cases, President Rousseff decides to invite her mentor, Lula, to join the government. A move seen as a last-ditch attempt to save her coalition. At the same time, members of the federal police, under the orders of the prosecutors, wiretapped – outside any legal framework – the phones of Lula’s lawyers (twenty-five defenders in all), as well as the former president’s own cell phone. Sergio Moro will thus obtain a conversation between the latter and Dilma Rousseff. An exchange with sibylline words about Lula’s future, which the magistrate promptly sent to Globo television and which sealed the impeachment of the president a few months later.

During this troubled period, DoJ prosecutors were closely monitoring political developments in Brazil. According to Leslie Backshies, then head of the FBI’s international unit, which since 2014 has been responsible for assisting the “ Lava Jato ” investigators, “ agents need to be aware of all the potential political ramifications of these cases, because international corruption cases can have major effects that influence elections and economies. ” The expert added, “ In addition to regular conversations about cases, FBI supervisors meet quarterly with DoJ attorneys to review potential prosecutions and possible consequences. ”

It is therefore with full knowledge of the facts that the latter finalize their indictment against Odebrecht in the United States. However, the group’s owners are reluctant to sign the “ collaboration ” agreement proposed by the US authorities, which includes the recognition of acts of corruption not only in Brazil, but in all the countries where this construction giant is established. To bend them, US prosecutors asked Citibank, in charge of the accounts of the company’s American subsidiary, to give Odebrecht 30 days to close them. In case of refusal, the amounts placed in these accounts will be placed in receivership, a situation which would exclude the conglomerate from the international financial system and would therefore place it in a situation of bankruptcy. Odebrecht agrees to “ collaborate ”, allowing the Lava Jato prosecutors, who have no jurisdiction to judge acts of corruption that took place outside Brazil, to obtain the plea bargains of the company’s executives. These confessions will later enrich the DoJ’s indictment under the FCPA.

The press release was published on Christmas Eve in 2016. The “ Lava Jato ” operation is on the front page of the international press. Sergio Moro is included among Time’s list of the 100 most influential people in the world. The New York weekly Americas Quarterly devotes its cover to him. For their part, the DoJ prosecutors publicly welcome this unprecedented cooperation. On the occasion of a conference held at the Atlantic Council think tank in Washington DC, Kenneth Blanco, then acting assistant attorney general of the DoJ, said that “ Brazil and the United States have worked together to obtain evidence and to build cases”, and that ”it is difficult to imagine such intense cooperation in recent history as that which has taken place between the DoJ and Brazilian prosecutors.”

Moro and the prosecutors start 2017 with confidence. Not that they obtained damning evidence against Lula – their private conversations via Telegram prove the contrary – but rather because their political and media influence is such that they will push their advantage, sometimes in defiance of the most basic principles of law.

Threats from the army

When Lula was convicted of “ passive corruption and money laundering ” on July 12, 2017, few journalists mentioned the fact that these charges were pronounced “ for indeterminate facts. ” Yet the argument is explicitly stated in the 238-page document detailing Moro’s decision. In the annexes to the conviction, the magistrate states that he “ never claimed that the amounts obtained by the OAS company through contracts with Petrobras were used to pay undue benefits for the former president. ”

Another oddity that reveals the weight acquired by the “ Lava Jato ” operation in the Brazilian judiciary: the incarceration of the former president takes place, on April 7, 2018, even though it is contrary to the Brazilian Constitution. Article 5 says that no one can be imprisoned before the end of the proceedings. However, under intense pressure from public opinion won over by the “ Lava Jato ” operation, the Supreme Court changed its jurisprudence on the matter in 2016, allowing his imprisonment. Lula’s lawyers habeas corpus request was rejected by a six-to-five vote in April 2018, following a tweet from the army commander threatening the Supreme Court to “ take its institutional responsibilities ” in the event that this would come to rule in favor of the former president.

Hours after the justices’ decision, Sergio Moro issues his arrest warrant. Lula will not be able to participate in the 2018presidential election. While the magistrate seems to be won by hubris, the infernal machine is launched. Jair Bolsonaro won the presidential election hands down and appointed the man who eliminated Lula to head the Ministry of Justice. On the American side, they are pleased to have brought down the corruption schemes set up by Odebrecht and in Petrobras, as well as their capacity to strengthen Brazilian political and economic influence in Latin America.

For the Curitiba prosecutors, the DoJ plans to pay them 80% of all fines imposed on the oil group under the FCPA, which they could be able to administer as they see fit. A private law foundation is to be created to manage 50% of the money. The board members of this foundation are none other than the Lava Jato prosecutors themselves and several NGO leaders, including those of the Brazilian chapter of Transparency International, which has become one of the main spokespersons for the operation over the years. Two of the team’s prosecutors, Mr. Dallagnol and Roberson Pozzobon, are even planning to create a legal structure in the name of their respective spouses, in order to bill for “ anti-corruption ” consulting services.

Whistleblower arrested

The international press will not take long to distance itself from the star of Curitiba. It came to emphasize his ethical inconsistency in forming an alliance with a far-right president, who for decades had been a member of an obscure party, known above all for having been involved in countless corruption cases. For their part, the Supreme Court justices do not hide their amazement when they learn, in March 2019, the content of the agreement negotiated in secret between the “ Lava Jato ” prosecutors and their DoJ counterparts. Justice Alexandre de Moraes will decide to suspend the creation of the “ Lava Jato ” foundation and place the hundreds of millions of dollars in fines paid by Petrobras into receivership.

It is in this context that The Intercept’s first revelation unfolds. In May 2019, Greenwald received from a whistleblower, Walter Delgatti, 43.8 gigabytes of data of private conversations, via Telegram, from the “ Lava Jato ” team. After verification work, three articles are published on a Sunday in June. Moro and the prosecutors do not recognize the veracity of the exchanges. They claim to have committed no illegality, while refusing to hand over their phones for examination.

Several weeks later, when Mr. Greenwald decides to offer access to the data to several media outlets, we learn in a government press release that Sergio Moro visited the United States from July 15 to 19. Did he take advantage of this visit to consult his counterparts? US authorities, requested by Agência Publica, will refuse to confirm or deny the information. Still, Mr. Delgatti was arrested shortly afterwards by the Brazilian federal police.

Read also: Former Brazilian President Lula released from prison after more than a year and a half in jail.

Although these revelations did not significantly affect the judge’s popularity, his aura continues to erode in the international press. For its part, the Supreme Court finally recognized the unconstitutional nature of Lula’s imprisonment. He will be released on November 8, 2019. The President was acquitted on seven of the eleven charges against him (the prosecution is appealing in four cases). Lula has yet to be tried in four cases that specialists consider of less importance.

Sergio Moro eventually resigns in April 2020. Brasilia’s political elite turns their backs on him, and the polls are reversed. A tiptoe departure follows, heading to Washington, where he replicates the revolving door model, which allows former DoJ prosecutors who have worked on FCPA-related cases to sell privileged information obtained during their investigations to large law firms, and to earn a lot of money. The announcement comes in November 2020, during municipal elections in Brazil. We learn that the former little judge from Curitiba was recruited by the law firm Alvarez & Marsal. An agency specializing in business advice and litigation whose headquarters in the federal capital is located at 15 Shet NW, just across from the U.S. Treasury and 200 meters away from the White House.

Les dates

2003 Lula (Parti des travailleurs) est investi président du Brésil. En juin, création des cours spécialisées dans la lutte contre les crimes financiers et le blanchiment d’argent. Sergio Moro est nommé à Curitiba.

2007 Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva commence un second mandat.

2008 Création par l’Ambassade des Etats-Unis du «Projeto Pontes », programme de formation des juges, procureurs et hauts fonctionnaires brésiliens dans la lutte anti-corruption et blanchiment d’argent.

2011 Dilma Rousseff (PT) succède à Lula à la tête de l’Etat.

2013 Vote par les parlementaires brésiliens de la loi anti-corruption. En juillet, reprise par Sergio Moro des enquêtes concernant les hommes d’affaires Alberto Youssef et Carlos Chater, qui conduiront à l’opération « Lava Jato ».

2014 Lancement de l’opération « Lava Jato ».

2016 Michel Temer (Parti du Mouvement démocratique brésilien) succède à Dilma Rousseff, destituée le 31 août. Mise sur écoute illégale des avocats de Lula.

2018 Le 7 avril, Lula est emprisonné.

2019 Jair Bolsonaro (Parti social-libéral) est investi président. Premières révélations du site The Intercept sur « Lava Jato ». En novembre, libération de Lula.

2021 En mars, annulation des condamnations de Lula.

[ad_2]

Source link

Have something to say? Leave a comment: